Women had to prove innocence; men (usually) got off lightly

Marlies Couch’s graduation thesis won three awards

For her undergraduate thesis at the University of Amsterdam, Marlies Couch, now a PhD researcher at the Huygens Institute, examined the social, medical and legal position of women in early modern times. By cleverly searching the online archives of the Old Bailey criminal court in London, among other sources, she managed to save the stories of women and the systems that marginalised them from oblivion. This work won her no fewer than three awards.

Image: Before, William Hogarth, 1730–1731. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

‘Gender inequality is deeply rooted in the past. That is no excuse, but it may help to put today’s difficult struggle for emancipation into perspective,’ says Marlies Couch about what is known as a “wicked problem”, a complex and persistent issue with no clear solution.

‘It is linked to a broader system of power and economic inequality, which almost inevitably translates into the oppression of women. Unfortunately, sexual violence is one way in which this has been expressed for centuries.’

Marlies Couch stands in front of the Amsterdam Spinhuis, a former women’s prison from the 17th and 18th centuries that now houses the Huygens Institute.

For her thesis, She Procured a Couple of Chirurgions: Unearthing Social and Medical Care for Survivors of Sexual Violence from the Old Bailey Proceedings, 1674–1800, Marlies Couch combined social, medical, and legal history to gain insight into the position of women in the early modern period.

Marlies Couch explains, ‘Rape and sexual assault were crimes in England, but convictions were rare. The burden of proof lay entirely with the victims, who also had to adhere to the prevailing socio-cultural norms that applied to women. Otherwise, they risked damage to their reputation, with all the consequences that entailed. Women were extremely vulnerable if they reported sexual violence. That is why they rarely did so. Nevertheless, women found ways to talk about it, and there was solidarity among them.’

Women’s history is challenging because women are less visible in historical sources. However, the tasks and activities that women performed can often be discovered by analysing commonly used sources (such as court cases) in a different way. Using a verb- or task-oriented approach, Marlies Couch discovered the care provided by women, including midwives, who played an important role in the administration of justice in the late 17th and early 18th centuries.

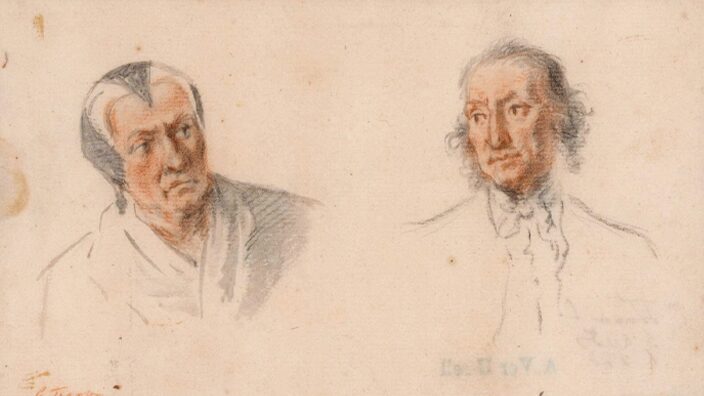

Midwife Jannetje Cabas and Foberts’ father in court, Cornelis Troost, 1741–1745. Rijksmuseum collection. This is a scene from the comedy Beslikte Swaantje, en Drooge Fobert; of de boere rechtbank (The Pregnant Swaantje, and Dry Fobert; or the peasant court) by Abraham Alewijn (1715), in which the question of who made Swaantje pregnant is investigated.

Marlies Couch explains that midwives testified as medical experts, examining victims of sexual offences and reconstructing the possible circumstances. ‘They also provided care. For specific rape wounds, for example, they used ointments, clay pastes, and pills made from coniferous tree resin. It is striking that untrained women also applied these healing methods.’

This suggests that midwives were an important professional group

‘At the time, midwives specialised not only in pregnancy and childbirth. They were important caregivers and possessed a wealth of empirical knowledge. During the 18th century, however, they gradually lost prestige after men with university degrees entered medical sectors where women had previously dominated.’

‘Women would apprentice with experienced midwives for training, sometimes for as long as ten years. However, this oral transfer of knowledge became less common as university-educated male doctors became more prevalent. Consequently, midwives were less often called upon to assist as medical experts in court cases.’

Solidarity among women

In the recent American civil lawsuit brought by journalist Jean E. Carroll against Donald Trump, who sexually assaulted and allegedly raped her in a department store changing room in 1996, the court based its ruling on the testimony of several women.

In addition to Carroll’s own testimony, two friends said they had been informed shortly after the incident. Other women also testified that they had been assaulted by Trump. Marlies Couch notes that you see something similar in the early modern period. Women and girls aged 10 and above had to prove that they were not to blame for abuse, assault or rape.

‘The burden of proof lay with them, not the perpetrators. That is why victims carefully crafted narratives that placed the responsibility on the accused men, using language that would not damage their own reputation.’

Such as?

‘She had screamed, resisted and shouted no and stop. Many accusations followed the same pattern, using similar wording. Other women acted as eyewitnesses and provided support. This suggests that women were telling each other what to say to the judge. Yet this rarely led to a conviction; the men usually went free.’

What happened to those women?

‘I think we are too quick to assume that victims of sexual violence were treated as outcasts during this period. While this was certainly the case for some, it was wonderful to discover in the sources that neighbours, friends, family members and midwives supported the victims in various ways.’

Why do you consider this to be a wonderful discovery?

‘It is valuable to know that, even in the past, women had ways of supporting and standing up for each other against male violence and unequal treatment. Until recently we viewed women of the past as helpless victims. It is wonderful to be able to recognise their strength and the control they exercised, though they had limited power. I am honoured that my thesis helps to raise the profile of these women. Their stories have finally been recognised.’

Marlies Couch received three awards for her thesis

UvA Thesis Prize 2025

Sister Vernede Thesis Award 2025

Johanna Naber Award 2025

PhD research into migrants employed by the Dutch East India Company and those who stayed behind

As a PhD candidate at the Huygens Institute and Radboud University, Marlies Couch is tracing the lives of migrants employed by the Dutch East India Company. Her research focuses on the challenges these migrants encountered after migrating to the Dutch Republic, as well as the opportunities they had to improve their socio-economic circumstances. The research will also examine migrant networks in Amsterdam and how the wives of seafarers coped with uncertainty regarding income and return.

Sexual violence and Dutch law

Even today, victims of sexual offences remain vulnerable. Often, there are no witnesses, and the Dutch Public Prosecution Service must provide convincing evidence. Since the Sexual Offences Act 2024, sex without consent has been a criminal offence; however, if the suspect denies the allegations, additional evidence is still required. Without this, it often remains a case of “one person’s word against another’s”.

If you or someone close to you has experienced sexual violence, you can contact (anonymously) the Dutch Sexual Assault Center on 0800-0188. Or you can visit the website.