The legacy of the VOC on Java: how colonial structures live on in today’s economy

In October, Mees Lammers began his PhD research into the long-term effects of Dutch colonialism on the Indonesian island of Java. As part of the Enduring Empire research group, he is investigating how the presence and activities of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries are still visible in today’s economic and social structures.

Before starting his PhD, Lammers first studied econometrics for a year. ‘I loved mathematics,’ he says, ‘but I missed the context. Data and models are interesting, but without historical background, it felt empty.’ He then went on to study history and quickly became fascinated by economic history, which combines quantitative methods and historical analysis.

During his Master’s degree in Economic History at the London School of Economics, he delved into the relationship between colonial institutions and economic inequality. There, he became particularly interested in persistence studies. This concerns how historical structures continue to influence the current economy. That approach now forms the basis of his research into the VOC in Java.

What is your PhD research about?

Mees Lammers: ‘We are trying to understand why some former colonial societies are richer or poorer than others today. The economic theory we use for this was developed by economists Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson, who received the Nobel Prize in Economics for their work. According to AJR, the distinction between settlement and trading colonies is an important predictor of later economic growth: settlement colonies tend to develop inclusive institutions that stimulate economic development, while trading colonies often remain stuck in extractive institutions that lead to long-term economic backwardness. In settlement colonies, such as Australia and Canada, Europeans settled permanently and built institutions that encouraged property rights and entrepreneurship. Trading colonies, such as Sri Lanka and India, on the other hand, were primarily focused on the extraction of raw materials and labour.

What kind of colony was Java?

‘The VOC was typically a trading organisation. It did not want to build a state or promote social development, but to make a profit. Batavia, now Jakarta, became the economic and administrative centre. The rest of the island mainly served as a supplier of cash crops such as coffee. However, the reality is less black and white. The VOC introduced different forms of government in different places. Within Java, there is considerable local variation, which makes it interesting from both a historical and econometric perspective.

How can you measure such colonial differences?

‘Until recently, that was almost impossible, but now the five million letters, logbooks and administrative documents of the VOC have been digitised and made searchable. This means that, for the first time, we can analyse on a large scale where the Company was active and what its trade network looked like.’

How does that work?

‘Using text recognition and machine learning, we search for clues in the source texts: which ships sailed where, which products were traded, and where did the VOC force local farmers to produce? That data is then linked to contemporary economic data. We want to know whether areas that were heavily integrated into the VOC network at the time are richer or poorer today. In this way, we are trying to literally map the impact of colonial institutions.’

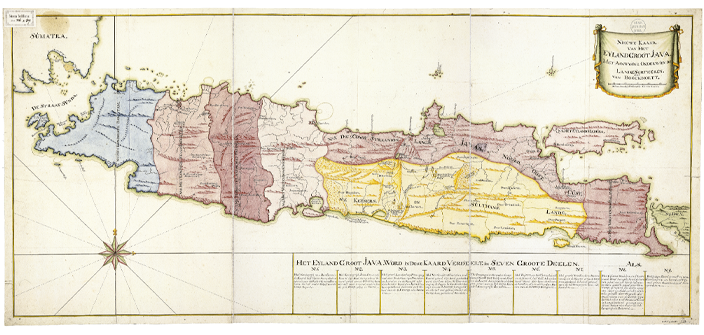

A map of Java, created by the VOC in 1761, showing how the island was divided and which parts were under VOC rule and which were not. Leiden University Library, Bodel Nijenhuis Collection 006-12-021. By Van Boeckholtt [after 1761]: New Map of the Island of Great Java, with an indication of who ruled which lands.

You work with figures, but also with historical sources. How do you combine the two?

‘Economics and history complement each other. Figures allow you to discover patterns, but you have to understand what those figures mean. That is why we combine quantitative analysis with qualitative interpretation of letters and documents. Sometimes you see an effect of “extraction” in the data, but then you also have to check the sources to see what actually happened. Was it forced labour, or rather a form of cooperation with local rulers? By combining both perspectives, you avoid squeezing history into an overly simplistic model.’

Why is that important?

‘It’s not just about economic growth, but also about social effects. The VOC may have reinforced social distrust in some places. If people have worked under duress for centuries or had little say, this can affect their trust in institutions today. Something like that is passed on from generation to generation.’

What do you expect your research to show?

‘Above all, I hope we can demonstrate that colonial policy patterns are still visible in the spatial inequality on Java. Jakarta is now the economic centre of Indonesia. This can probably be traced back to the time of the VOC, because that is where its headquarters were located. At that time, substantial investments were made in infrastructure, administration and trade, while the interior was neglected.’

Do you expect clear conclusions?

‘We are not trying to draw a simple line from “colonialism causes poverty”. The point is to understand how economic and institutional structures continue to have an impact in the present. To investigate this properly, we are collaborating with Indonesian universities and the national statistics office. Local researchers often have a better understanding of how the past continues to influence culture and society. Their perspective is indispensable in this research.’