Suriname Time Machine

| Duration: | 2025-2026, with possible extension |

| Subsidy provider: | Pica Foundation |

| Subsidy size: | 150.000,- euro |

Historical data from the 19th century on

1 interactive map

The Suriname Time Machine brings together scattered sources. Users can access everything in one place, without constant cross-checking whether data refer to the same people, streets or plantations. Easy research helps to reveal broader patterns, such as those linked to migration and slavery, and makes it easier to trace individual family histories.

Take, for example, a portrait from the Rijksmuseum collection. It shows the Surinamese couple Johannes Ellis and Maria Louisa de Hart, painted in 1846, the year their marriage took place. He was 33 at the time; she was 19. The caption notes that he was born in Ghana, but her origins are unknown.

A little online digging tells us more. Johannes Ellis was born in Fort Elmina (present-day Ghana) and moved to Suriname, where he became a civil servant in the 1830s. Maria Louisa was the daughter of Mozes Meijer de Hart, a Jewish merchant. She was born into slavery, but freed by her father at a young age. The couple lived in Keizerstraat, one of Paramaribo’s most prestigious addresses. They had five children, one son and four daughters.

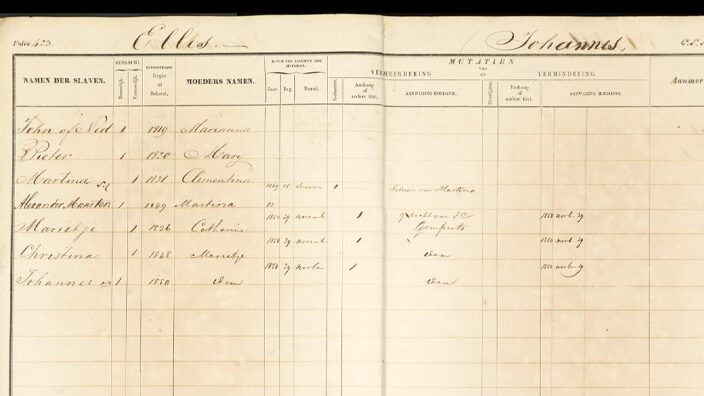

Like many middle- and upperclass households in 19th-century Suriname, they owned enslaved people: in 1846, their household included three men, two women and five children. One of these women, Marietje, was the same age as Maria Louisa and had two young children of her own.

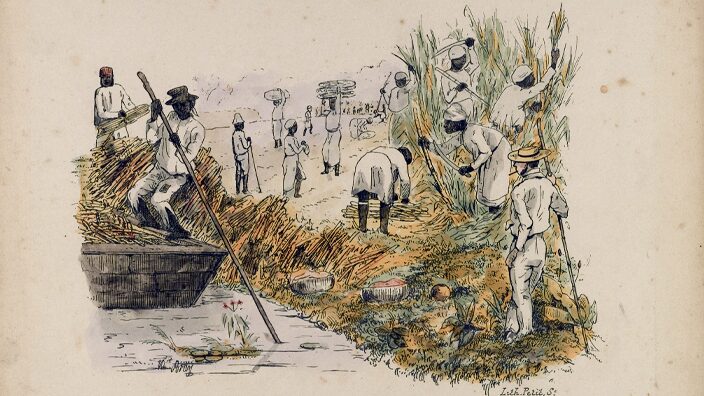

The couple were also co-owners and managers of the Sardam sugar plantation, located on the Cottica River. According to the 1847 Surinaamsche Almanak, around 200 enslaved people were forced to work there. An old newspaper clipping suggests the couple still partially owned the plantation in 1868. When slavery was abolished in 1863, 287 people were freed from Sardam.

This kind of information comes from a variety of sources: the Civil Registry of Suriname, the Paramaribo Ward Register, the Slave Register (available via the National Archives of Suriname), the Emancipation Register (Netherlands National Archives), and digital collections like DBNL and Delpher, managed by the Royal Library of the Netherlands. Reconstructing the story of a family like Ellis-de Hart means painstakingly piecing together fragments from all these different archives.

Suriname Time Machine

This is what the Suriname Time Machine is designed to solve. The project aims to bring together these disparate datasets in one central hub. This makes it easier to uncover stories like that of Ellis and de Hart. Surely, wealthy individuals like them tend to leave more records, but by linking sources, we can also start to uncover the lives of those who left fewer traces, like people of modest means and those who lived in slavery.

Everything in one place

The Time Machine integrates an ever-expanding set of databases from Suriname’s past, maintained by different heritage institutions, into a single digital map. Researchers will be able to work more efficiently and accurately. Those tracing their family roots will have an easier time locating records, even when names or addresses have changed.

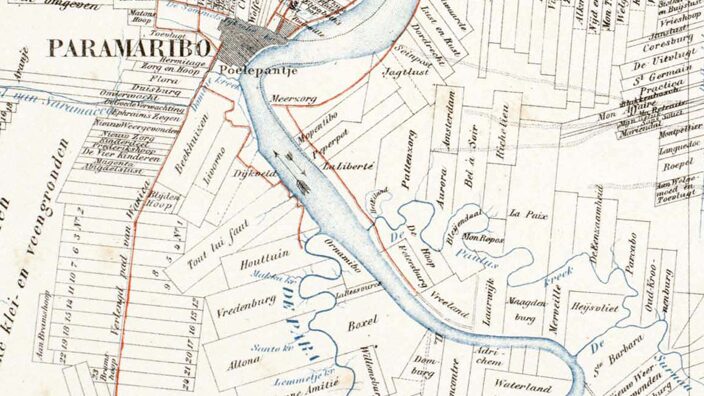

Institutions like the Rijksmuseum can also benefit: a tool like this allows them to better contextualise objects in their collections, whether a portrait like the one of Ellis-de Hart, or an image of a plantation. This is particularly useful in a country like Suriname, where multiple plantations often shared the same name. At least five plantations were named Libanon, each located on a different river or creek.

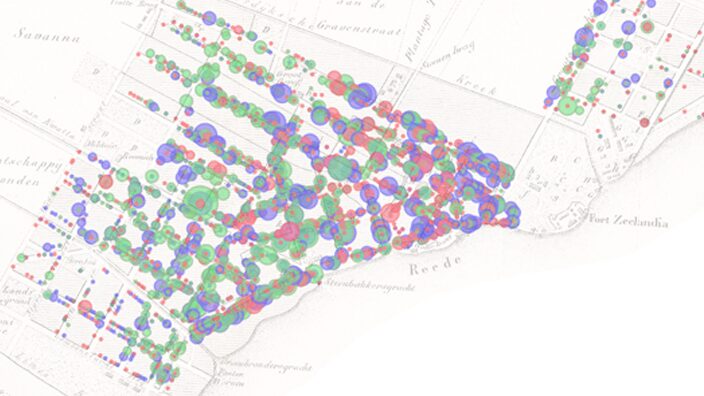

A map of Paramaribo from 1846 showing, by address, the ethnicity of both free and unfree inhabitants, based on the skin colour classifications used in that year’s District Register. Blue represents residents of African descent, red indicates (white) Europeans, and green denotes individuals of mixed or indigenous heritage. The larger the circle, the greater the number of inhabitants.

The Suriname Time Machine draws inspiration from the European Time Machine, which fuses technology and heritage to digitally reconstruct the histories of cities and societies. While similar projects exist in the Netherlands, like the Amsterdam Time Machine and Gouda Time Machine, this one looks beyond Europe, turning its focus to a country in the global South.

Project team

The Suriname Time Machine is led by researcher Thunnis van Oort, together with Gerhard de Kok of Datacollecties. Van Oort previously worked on the Historical Database of Suriname and the Caribbean (HDSC), a large-scale research project based at Radboud University, in which hundreds of citizen scientists helped digitise historical records.

In 2023, the digitised slave registers of Suriname and Curaçao, developed through the HDSC, were internationally recognised and added to UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register, the UN’s programme for the preservation of documentary heritage. HDSC is one of the key partners in the Suriname Time Machine.

Digital infrastructure

The project’s digital infrastructure is built on Linked Open Data principles, ensuring that datasets are interoperable and openly accessible. The platform is designed to grow continuously, with new collections and sources being added over time. The underlying technology will also be adaptable for future use in other regions, for example the (former) Netherlands Antilles.

Partners

The Suriname Time Machine is not only a digital platform but also a collaborative network, connecting a wide range of heritage institutions and researchers in both Suriname and the Netherlands. Project partners include:

- National Archives of Suriname

- National Archives of the Netherlands

- Foundation for Surinamese Genealogy

- Philip Dikland, architect in Paramaribo and curator of the Suriname Heritage Guide

- Historical Database of Suriname and the Caribbean (HDSC), Radboud University

- Amsterdam Time Machine, University of Amsterdam

- Allard Pierson Museum and Library, UvA / HvA

- Leiden University Library

- International Institute of Social History

- Wikidata

A detail from a 19th-century map of Suriname shows how Paramaribo was once surrounded by plantations. The Suriname Time Machine brings this kind of historical data digitally to life, making it easy to search and explore.