Huygens Director Dirk van Miert appointed professor in Utrecht

From August 2025, Dirk van Miert will hold the special chair in History of Knowledge from a Digital Perspective at Utrecht University. He is also director of the Huygens Institute for Dutch History and Culture. The leading research institute has special expertise in digitisation, accessibility and interpretation of historical sources and archives. ‘I sometimes compare our digital tools to the newest space telescopes: they allow us to look much deeper into the past, enabling major new discoveries in the humanities.’

Cultural historian with a digital perspective

Dirk van Miert is a cultural historian and Latinist. He has been director of the Huygens Institute since 2022. From August 2025 he takes up a professorship in Utrecht. In his field, historical sources are being digitised on a large scale and made accessible for groundbreaking research. Van Miert: ‘Not only for scholars, but also for the general public.’ This is in line with the national digital heritage strategy (2025–2028).

Groundbreaking historical research

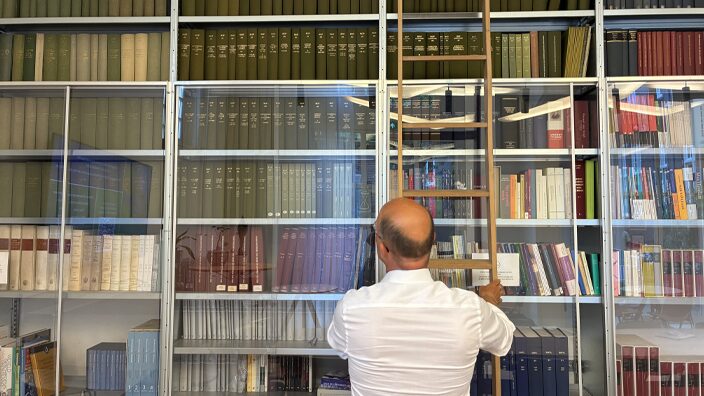

This digital revolution builds on a long tradition at the Huygens Institute. For more than a century, the institute has been engaged in publishing and interpreting historical sources and literary texts. The ‘Big Green Volumes’ of the Rijks Geschiedkundige Publicatiën (RGP) in which the historical sources were published are well known. Today, the elegant green bindings ornament a wall in the institute’s common room, partly behind protective glass.

Digital access involves turning raw paper documents into structured, accessible information that can yield knowledge. This raises questions: how was this data collected, selected and passed on? What information is lost and who makes these choices?

Ethical questions versus conspiracy theories

Van Miert: ‘Historians and edition scholars who publish sources and develop databases analyse all steps in the process, from data selection to interpretation, and ask the ethical questions that go with them. This is important for research and for society at large. Because we all gain knowledge from the data we download to our phones every day. If you handle this carelessly, you quickly end up with misrepresentation, fake news and conspiracy theories.’

‘I sometimes compare our digital history tools to the newest space telescopes.’ Dirk van Miert at the Huygens Institute.

Major new discoveries

The digitisation of sources is a huge asset to the humanities. Smart scanners unlock miles of archives and millions of forgotten books. This allows researchers to search faster and find much more. ‘This unearths facts and stories that change our view of history and the world.’ The digitisation of the VOC archives, for example, has yielded a wealth of new information about the early modern history of Asia, Africa and Australia, as well as about economics, culture and ecology. ‘Especially about cultures and groups that previously remained invisible.’

Like the newest space telescopes

Van Miert: ‘I sometimes compare our digital tools to the newest space telescopes: they let historians look much deeper into the past. But just as many mathematical calculations are needed before we can understand what a real space telescope actually shows us, converting old sources to a digital environment requires a great deal of knowledge about the historical context. Who wrote this, when, where, for whom, for what purpose, which modern translation is appropriate? That is why our digitisation projects are always accompanied by research into the ways knowledge is generated and transmitted.’

At the same time, digitisation raises new questions. Who manages the data, what new dependencies are created, and how do we prevent abuse and exclusion? Van Miert: ‘Also every archive is a product of its time, so a modern audience can never take conclusions at face value. We need to know something about the context.’

Context is crucial

The recent release of sensitive World War II files from the CABR (Central Archive for Special Criminal Justice) shows how important context is. Digital search functions offer new historical insights and can provide answers for next of kin, but interpretation must be done carefully. Van Miert: ‘We must be sure that our interpretation is consistent with what is actually there, with what is not there and with what is implied between the lines. Providing context is essential. We can use pop-ups to explain, clarify or highlight connections. We pay a lot of attention to this at the Huygens Institute, we even develop special software, partly using AI’

Technological revolution versus unchanged power structures

His professorship also addresses the tension between digitised sources and context. Van Miert: ‘We are in the midst of a technological revolution, but our social power structures have barely changed. Who manages our data? What role do tracking, surveillance and archives play in power relations? Without ethics and historical reflection, we risk digital data being misused or interpreted in skewed ways, just like the paper archives of the past. So I will impress upon my students, the new generation of text and archive scholars, that they are just as essential as young tech specialists.’