Medieval people were not too concerned about forgeries

The rich yield of a scientific discipline going extinct

Sifting through legal documents may seem tedious, but nothing could be further from the truth. The Limburg Charters reveal a surprising abundance of information about daily life in the Middle Ages. Geertrui van Synghel of the Huygens Institute unlocks these sources and uncovers stories about governance, disasters and everyday events, such as a dispute involving a miller and his horse. She is now the only person in the Netherlands who still possesses this specialist knowledge.

Image: Geertrui van Synghel shows a Limburg Charter to the dean of St. Servatius Basilica, the bishop of Roermond and the papal nuncio in Africa, guests of honour at the presentation of the Charter Book of the St. Servatius Chapter and the opening of the accompanying exhibition in 2025. Photo: Jean-Pierre Geusens for the Heiligsdomsvaart in Maastricht.

Just like some crafts, there are also scientific disciplines that are becoming extinct. When researcher Geertrui van Synghel, who has been associated with the Huygens Institute for more than 40 years, began cataloguing the North Brabant Charters in 1979, she had five colleagues. Now she is the sole individual with the knowledge and expertise to read, understand and publish charters written in Latin.

The last woman standing. Charter studies have disappeared from university curricula. Latin is no longer compulsory anywhere. Van Synghel fully understands: “How can a young scholar earn a living from charters? I have been fortunate. And I too do most of this in my spare time.

Palaeography and charter studies

Van Synghel’s official areas of expertise are palaeography and charter studies. Palaeography is the study of ancient manuscripts. Charter studies focuses specifically on the form, structure, function, origin and authenticity of charters in order to understand how medieval administration and jurisprudence worked. This requires a great deal of contextual knowledge, ranging from political history to social developments.

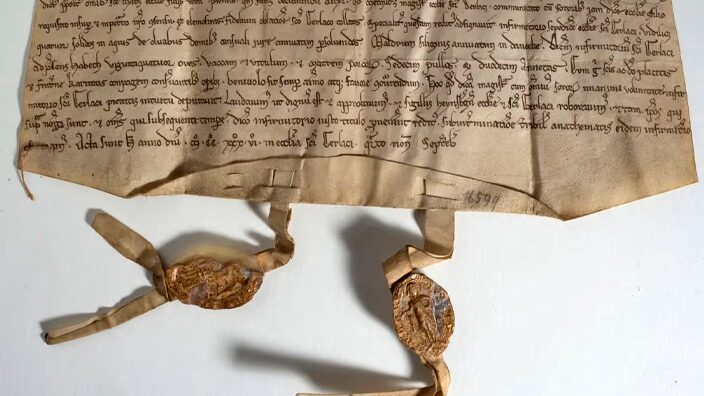

Deed number 5 from Sint-Gerlach, 2 September 1236. Mathilde, magistra of Sint-Gerlach, allocates an annual rent of four schelling and a malder of rye to the Sint-Gerlach infirmary. Image: Waarvan Akte website.

Research in multiple sources

For each charter, Van Synghel delves deep into the archives, searching for relevant sources that can reveal the true meaning of the document. This detective work has earned her the unofficial title of “sleuth”: ‘It’s sometimes such a complicated puzzle that I feel like a detective gathering pieces of information from everywhere.’

Limburg Charters: academic edition and public version

Since 2018, she has been working on the academic edition of the Limburg Charters, with a printed academic publication every year. In the summer of 2025, volume 4 was published and there was an exhibition (of short duration, due to the fragility of the charters) at the Zusters Onder De Bogen in Maastricht. The digital edition of the Limburg Charters is posted online on the Waarvan Akte website, including accessible public versions and stories.

From collapsed bridge to a miller’s horse’s arrest

Van Synghel draws a wealth of stories about Limburg in the past from the charters. From the great disaster at the Servaasbrug in 1275, which claimed 400 lives and led to a crowdfunding campaign to rebuild the bridge, to the curious arrest of a miller’s horse, which was released after the clergy of Sint-Servaas intervened.

Image of a miller and his horse from the Romance of Alexander (1338-1344). Bodleian Libraries Collection.

Every letter measured and analysed

Thanks to her meticulous research, Van Synghel has even been able to demonstrate that a number of charters previously considered to be forgeries are probably genuine after all. These charters were claimed to have been drawn up by a single person who was not even born when the documents were dated.

Through meticulous palaeographic research, in which she examined the manuscripts closely and measured every letter from all angles, Van Synghel was able to determine that the charters had been written by different hands (and therefore probably by several people). So they were not forgeries after all.

‘As an experiment, I am now having these charters examined by AI. I am very curious to see what the results will be.’

Postdating centuries later is also legally valid

‘But medieval people weren’t so bothered about forgeries,’ she adds. ‘If verbal agreements had ever been made, for example about land ownership, there was no objection to drawing up a charter centuries later. Nowadays, we find that dubious or unacceptable; at the time, they regarded it a legally valid confirmation.’

Discover more

View the Limburg Charters and read the stories on the Waarvan Akte website.